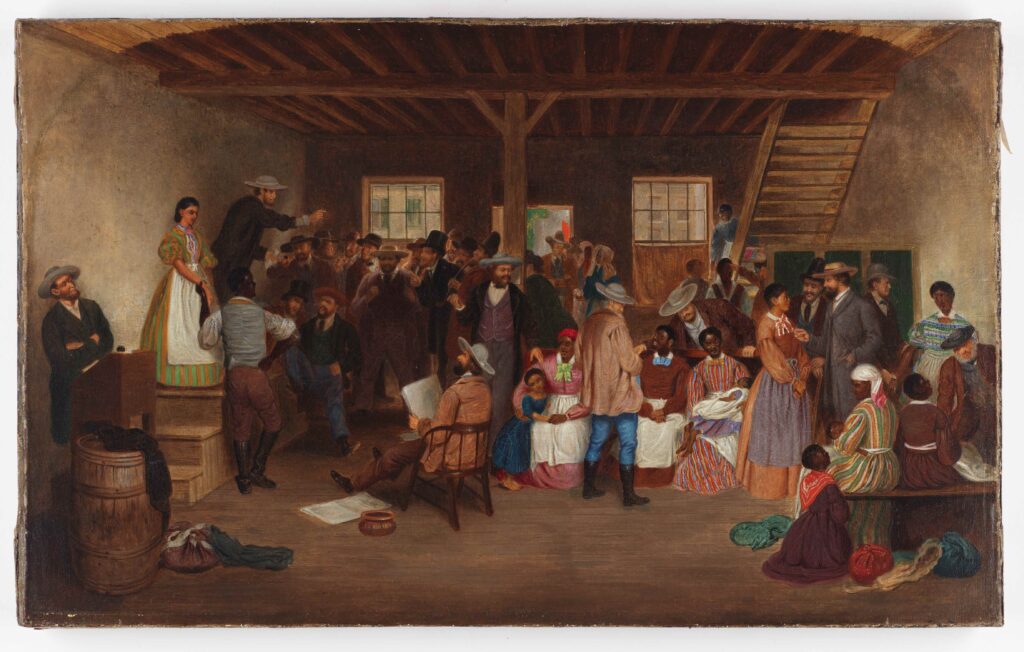

Slave Auction in Operation – Richmond 1861

Slave Auction, Virginia 1861. Oil painting by Lefevre James Cranstone . Source: Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA

Lefevre James Cranastone was a respected English painter who was visiting America to record the sceney and the buildings. Like Thomas Jackson, he appears not to have searched out slavery but when he encountered slave markets in Richmond, he became obsessed with recording the scenes that he witnessed and so took extensive notes and did preliminary sketches while still in Richmond.

After he returned to England he completed this marvelous painting – in our opinion the best illustration of a slave market that exists.

His long, critical letter to his local English Newspaper recording his observations on politics and slavery in USA. In it, he explains in detail features that are clearly illustrated in this painting and probably were similar to those that TJ encountered when he first encountered a slave market about 20 years earlier.

There are many details that may not be obvious at first sight. First it is only the women slaves that are on display in this scene and they are much better dressed than you might expect. This is because each auction was staged like a piece of theater and the slaves dressed in fresh clothes and even given jewelry simply to make them look more attractive for the occasion.

Sickeningly this was particularly the case for relatively young women who were less black and could be seen as possible sex partners for the white purchasers. They were expected to be cheerful and look active and obedient. This slice of the slave auction was called the fancy market and the prices paid often exceeded that paid for healthy men.

We know that the male slaves were typically separated from the women prior to the bidding and usually each one was physically inspected in the mouth, on the back and over their torso. Scars on their back were considered as important indicators as to how valuable that particular slave might be. Many scars would be interpreted as an uncooperative individual (rather than a cruel master) and only old scars might indicate that the slave had reformed and was now obedient.

See how Cranstone’s account in his letter to the newspaper provides a powerful explanation for the details in this beautifully crafted painting.

But it is in the slave auction rooms where the horrors of the system are most palpable to the eye. No pen can adequately describe scenes so revolting to the mind of a stranger. It was in the month of March of this present year, that being at Richmond, Virginia, I turned down a back street and saw a row of dirty looking houses to the doors of which were posted red flags on which were pinned pieces of paper announcing the time of sale of the human merchandise within.

Entering one of these low dens in company with a motley crowd, the first object that met the eye was a company of coloured women and young girls, seated on benches awaiting the sale. The men and boys are placed behind a screen at the further end of the room, surrounded by an eager crowd of purchasers, each slave being stripped to the waist, that he may be tested as to soundness and bodily health. The sale room was long, dark and dingy, with a raised platform on one side for the salesman and the “lot.”

Awaiting the arrival for the auctioneer these goods are freely handled and inspected. Here is every shade of complexion from purest ebony to white, black field hands, yellow beauties, stout fellows; if the buyer wishes bright-eyed, smooth of skin, supple of form, full-chested, clean-limbed creatures, culinary prodigies, deft semptresses (sic), delightful washerwomen, charioteers, unrivaled, the very treasures of commercial Christianity; the only adequate exponents of Virginian wealth and enterprise.

The women are dressed in flaunting gay colours, the men in their best trim. The auctioneer arrives, the sale commences. I see one after another mount the platform— the men first, the women and children last. And they are quickly knocked down, showing a brisk demand in the market.

Whilst the sale is progressing each slave is subjected to a close examination; their arms and hands are felt— teeth inspected—made to walk up and down the room, and to mount and remount the platform. In spite of what is so often said in contradiction to the parting of families, I was an eyewitness that such is the fact; several young children and their mothers being knocked down to different purchasers.

With a long-drawn breath I follow the crowd out, who made their way to another room, where the same scene is enacted. Day after day these scenes are going on in the midst of churches and chapels, and within a stone’s throw of a splendid monument of Washington.

Extract from Cranstone’s letter to his local English newspaper “Hemel Hempstead Gazette1860-12-29”